VeloceToday.com Review

by Pete Vack, December 2014

Jacques Saoutchik Maître Carrossier

By Peter Larsen and Ben Erickson

All images are credited to the rights owners in the physical book Jacques Saoutchik, Maître Carrossier.

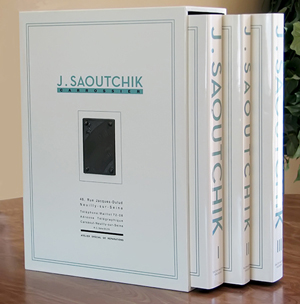

It is an honor for us to be chosen as one of the few to have received this book for review, and therefore our duty to do the best job of it, even if the run may be sold out before we review it! Already the awards are coming in: In association with EFG and Octane Magazine, the International Historic Motoring Award for Publication of the Year was awarded to Peter M. Larsen and Ben Erickson, the authors of Jacques Saoutchik, Maître Carrossier, at an awards ceremony held November 20th, 2014 at London’s St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel. It is an honor for us to be chosen as one of the few to have received this book for review, and therefore our duty to do the best job of it, even if the run may be sold out before we review it! Already the awards are coming in: In association with EFG and Octane Magazine, the International Historic Motoring Award for Publication of the Year was awarded to Peter M. Larsen and Ben Erickson, the authors of Jacques Saoutchik, Maître Carrossier, at an awards ceremony held November 20th, 2014 at London’s St. Pancras Renaissance Hotel.

Writing entirely in English, Peter Larsen brings to light the fascinating, human, often inspiring lives of Jacques and Pierre Saoutchik, father and son, from Jacque’s migration from Russia in 1898 to the last fateful days of the business under Pierre 1954. Larsen and Erickson comprehensively illustrate the coachbuilder’s art in three volumes, 1063 pages and 1933 images. Larsen had unprecedented access to the family files, convincing Saoutchik’s daughter-by-mistress to assist with her letters, photos and remembrances, and conducted a great deal of original research on the subject. Most importantly, when restorer David Cooper came into possession of a massive amount of Saoutchik archives, he kindly turned them over to Larsen and helper Ben Erickson. These formed the basis of the book.

Saoutchik was perhaps, arguably and subjectively, France’s greatest coachbuilder. While Larsen does not argue that point, clearly the automotive delights that Saoutchik created speak for themselves (in this case, volumes). For the first time, readers are treated to not only the exterior designs, but full and detailed photography of the interiors, which were after all, Saoutchik’s forte until the last Delahayes and Pegasos (which were more sporting than luxurious). The new and old rich of the world came to Saoutchik with a sybaritic (a word used often) appetite which seemingly only Saoutchik could satisfy.

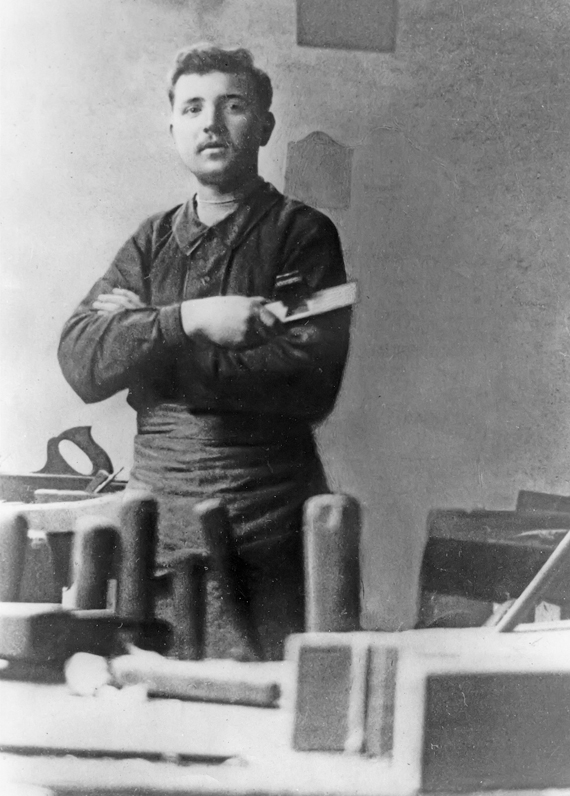

Jacques Saoutchik was a cabinet builder, having learned his craft as a young Russian in a small town some 62 kilometers from Minsk. He took his craft, his brother and little else to Paris in search for a better life, and by 1906 had applied his craft to then new/old industry of coachbuilding for the automobile, which caught both France’s and Saoutchik’s interest. The name, by the way, was changed along with location, for Saoutchik’s real name was Iakov Savtchuk. The family was Jewish, a fact Jacques never forgot, though tried to hide as he threaded his way through the Russian pogroms to the perilous Dreyfus years in France, all the way through to the German Occupation of France.

Of the three volumes, there is no doubt that Volume 1 is the most interesting, yet may be the most controversial. Larsen has done something relatively unusual in presenting the life of the Saoutchiks. The quickest way to describe this is to say that if one were to write a light but fairly comprehensive political and social history of France from the gay nineties to the 1950s, and within that framework drop remarkable anecdotes of the life of the Saoutchik family along the way, one would have grasped the format. Although not on par with a Barbara W. Tuchman, Larsen does a fine job as a historian but be prepared; although this reviewer definitely enjoyed the show, others, looking for more automotive-oriented text, may not. However, readers will learn much, and there is no doubt that to understand Saoutchik, one must understand the times. Larsen makes sure we do. With the ability to publish a full three volumes on the subject of Saoutchik, devoting a large number of pages to the background history seems perfectly justified.

A proud Jacques Saoutchik circa 1904 when he was just beginning his career as a coachbuilder.

Saoutchik’s life and career was affected by all the major events and they had a significant impact on his life; Russian pogroms, WWI, the twenties, the Depression, WII, the aftermath including imprisonment for collaborating with the Nazis. (It seems incongruous that a Jew would be known to collaborate with those who are bent on sending Jews to the concentration camps, so the charges were possibly unfounded.) Also the French social/economic necessities and political scene meant the end of the grand coachbuilders, none surviving for long aside from Chapron. Yet, despite a horrific century in terms of war and tragedy, Saoutchik led a fascinating life; he had success, he had mistresses per the customs of his class, raised a family and sired a son who eventually took over the business and for about 10 years, allowed the firm to flower once again, albeit insufficiently profitable. Life beyond the Pale was good.

After WWII, aging, facing prison time for collaboration, and not particularly enthralled with the new, streamlined and soon unit-bodied automobiles, Jacques took a back seat and allowed Pierre’s artistic skills create a new look and line for the company. He was also unhappy about other attempts to provide extra income for the firm by allowing the Saoutchik name to be used on products like car wax, as Gijsbert-Paul Berk was to find out firsthand.

Larsen relates this epic with both respect and understanding of the extremely complex issues of the times, from the Dreyfus Affair to the sad but to-be-expected backlash against anyone who was accused, rightly or wrongly, of collaboration with the enemy, including Renault himself, Bugatti driver Helle Nice, and Saoutchik. While this reviewer does not claim to be an expert in French and European history, Larsen has dealt with the non-automotive history with accuracy as well as fairness. He includes a lot of interesting characters and events in his description of France; most add to the overall portrait but others, like Bluebeard, seem out of place.

Near the end of Volume 1, Larsen engages VeloceToday Correspondent, artist, author (Andre Lefebvre) and longtime AutoVise editor Gijsbert-Paul Berk on a discussion of whether or not Saoutchik’s creations could be legitimately called art, particularly in reference to the post WWII designs. Though we agree with our correspondent Berk in that art must be for art’s sake alone, upon seeing page after page of both outrageous and outrageously beautiful designs that often just take the breath away, it is hard not to call it art, whatever the true definition may be. As Larsen argues, Saoutchik’s heavenly bodies engender a good deal of emotion, which art strives to do. Reader’s comments are welcome!

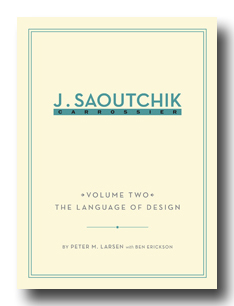

Having given the reader an understanding of the life and times of the coachbuilder, Volume 2 takes an unusual turn by presenting a series of brochures, ads, and overall descriptions of Saoutchik cars and offerings. It is deceptively sublime; Larsen states the intent is to provide a reference work in which the chapters can also stand alone, but he is even more correct in thinking that together, the brochures (dating from 1908!) and design studies will “constitute a comparative analysis of styles and complete design history of Sauotchik…” This is not your average brochure book! Having given the reader an understanding of the life and times of the coachbuilder, Volume 2 takes an unusual turn by presenting a series of brochures, ads, and overall descriptions of Saoutchik cars and offerings. It is deceptively sublime; Larsen states the intent is to provide a reference work in which the chapters can also stand alone, but he is even more correct in thinking that together, the brochures (dating from 1908!) and design studies will “constitute a comparative analysis of styles and complete design history of Sauotchik…” This is not your average brochure book!

Thanks to the Lilly Library and others, Larsen has assembled a rare collection of brochures which are superbly reproduced. The layout by Jodi Ellis enhances the presentation of the brochures and artwork. Somewhat simplistic at first, by 1925 the Saoutchik brochures had blossomed into four colors with slipcovers and Art Decoratifs renderings in folders; artists such as Georges Barbier, font artist Maurice Nicolas and Guy Sabran were responsible for the brochures depicting Mercedes-Benz, Hispano Suiza, and Bucciali.

The never-built Bucciali roadster, from a rare Bucciali brochure. Considered the apogee of the prewar designs, styling cues from the roadster would be used on later Hispano Suiza designs.

One can’t easily get an appreciation of this kind of work on the Internet, or even with a brief look-through. Settling in with the volume and taking each chapter with patience and care is simply a wonderful experience. The art, the colors, the Saoutchik lines, the interiors, and the atmosphere of the respective eras come across eloquently yet forcefully at times. All along Larsen not only discusses the brochure or design (a factory drawing of body which may or may not have been produced) but gives the background of the car and or cars.

Sadly, after WWII, there was no Saoutchik budget for such brochures and Larsen presents a series of design drawings and lacking that, uses ads or color images. The design art is almost as interesting as the full color brochures of the thirties, and represents the era of Pierre Saoutchik instead of his father.

Appendix III of Volume One is an essay with photos by David Cooper about the restoration of the Prim Delahaye 135M convertible. So interesting was the description of the body building technique that we asked Cooper if we could reprint it in VeloceToday; thankfully both he and Larsen complied, and we’ll have that for you in January.

For those of us who might be interested only in the products, designs, serial numbers, and fate of the known Saoutchik cars, Volume 3 is the most interesting of the three volumes, and exactly what one might expect of a high end-work on a single coachbuilder, make or model. Larsen takes this by year from 1906 and presents what information is available; not easy as there are no factory records to refer to (much of the Saoutchik company files were lost in a 1957 fire). The oldest surviving Saoutchik-bodied car is reckoned to be a 1913 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost Torpedo, a magnificent example of both chassis and body and well used yet today. For those of us who might be interested only in the products, designs, serial numbers, and fate of the known Saoutchik cars, Volume 3 is the most interesting of the three volumes, and exactly what one might expect of a high end-work on a single coachbuilder, make or model. Larsen takes this by year from 1906 and presents what information is available; not easy as there are no factory records to refer to (much of the Saoutchik company files were lost in a 1957 fire). The oldest surviving Saoutchik-bodied car is reckoned to be a 1913 Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost Torpedo, a magnificent example of both chassis and body and well used yet today.

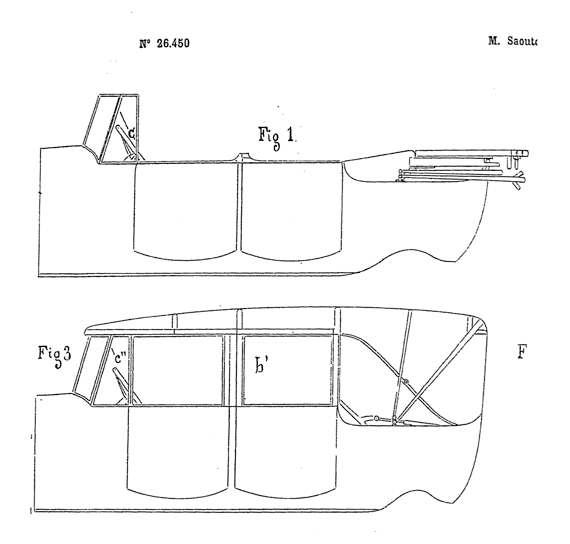

Saoutchik's patent drawings for 'improvements made to automobiles called convertibles' allowed the top to lay flat.

There were no cars built from 1914 to 1919, but the period from the end of the war to 1926 saw the rise of Saoutchik to new levels. Saoutchik concentrated on developing the transformable, a multi-use body which could be totally open, partially closed, or fully closed with a variety of front and rear windshields. He patented many of his top mechanisms and window hardware. His work was superb and his bodies were only fabricated for the finest chassis; Rolls-Royce, Voisin, Minerva, Mercedes-Benz, and above all Hispano-Suiza. Thankfully, Larsen allows us an inside look at the designs for the complex top mechanisms, and the for-royalty-only interiors that were the hallmark of the firm until after WWII. Today, when these cars are viewed at shows and in museums, these key elements often remain hidden, yet to appreciate Jacques Saoutchik one must appreciate the quality and style and material of his interiors.

The interior of a 1925 Hispano Suiza. The woodwork, leather (often in exotic hides) and fixtures were exquisite.

In 1927 Saoutchik visited Buffalo New York to see his brother and do a bit of lucrative consulting work for the critically-ill Pierce Arrow company. He returned to Paris enthused and inspired by things American. The following years would be his most creative. For Mercedes, he re-invented the ancient fiacre line with flair, and began the use of fender scallops tooled out of German silver, which would remain a motif until almost the very end in 1954. A beltline appeared and later extended arrow-like into the hood. Bodies for Duesenberg, Delage, Cadillac, Bentley, and the immortal Bucciali added to the long list of chassis. For a while, Saoutchik could do no wrong.

The worldwide recession caught up with France by the mid-thirties and orders fell off while streamlining became all the rage, much to Saoutchik’s dismay (although to his son’s delight). The great Hispano Suiza stopped making cars, while more bodies were built on less expensive chassis, and a brief attempt to create a production body for the Georges-Irat failed. Meanwhile, son Pierre got himself involved in the dramatic, beautiful and ultra-advanced Hispano Dubonnet Xenia II project, elements of which would show up after the war.

Sir John Gaul's Delahaye at the Concours de la Grande Cascade in 1949 illustrates the work of Pierre Saoutchik in the post war era.

Along the way Larsen mixes the best historic images with the best of current photography, much from the lenses of Michael Furman as well as our own Hugues Vanhoolandt. He tops off the last volume with an Appendix on Replicas, Recreation and Continuation Cars, and perhaps the most important, a listing of known Saoutchik-bodied cars (not a complete or representative tally of all the cars however), listed by make including the chassis numbers. This is followed by a wonderful set of indexes that get you any which way you want to go in the book.

It was not just the Pons plan that crushed postwar coachbuilders. Firms like GM could deliver complete automobiles which were faster, cheaper and more reliable than French cars; Cadillacs and Buicks were almost as decadently stylish as a Saoutchik. This is a GM advertisement.

Our only criticism, as the book(s) are nearly faultless throughout concerns footnotes, or lack thereof, which will probably not bother most readers one whit, but for those of us who must and often do sweat over details and search for sources, footnotes are invaluable references and reinforce the author’s hard hours of research while enhancing the work in the eyes of academia. Larsen does provide a complete (automotive) bibliography and an entire appendix on sources, clearly defining what libraries, people, and other sources were employed. There is little doubt that the research is valid, original, and properly done. We asked the author about the lack of footnotes:

“This is a very valid point. As you may know, I am an academic, and deeply schooled in how to conduct research and the how and the why of the almighty (and often indigestible) footnote. It was my decision not to have any. I feel that footnotes at the bottom of pages spoil the layout and make things look messy – especially when there are many images – and that when they are at the end of a chapter one is constantly flipping back and forth – only to discover that the note in question contains some obscure page reference that one doesn’t care about anyway. I feel that entertainment value must not be compromised over-much, while factual correctness must be maintained. So I decided to lay my main sources bare and discuss them in an appendix (as well as in the dedications) and include a very comprehensive bibliography which indicates the subject of the entry, so that readers can pursue further knowledge at their leisure. This decision was mine and I accept full responsibility.”

Something that must be said that is not a criticism but unfortunate; there are only 500 copies of this fantastic work; that means that only the first with the most will ever be able to own a copy. Not only that, all the run is sure to sell out quickly. We are at once thrilled and enlightened by the vast amount of fascinating material in Larsen’s work, while at the same time deeply saddened that such information can’t be disseminated in some form to the thousands of others who would love to learn more about the subject. We are fortunate to be able to allow readers some insight via this review and the reprinting of the essay on the restoration techniques by David Cooper (coming next month in VT).

Jacques Saoutchik Maître Carrossier is the Best Italian/French subject book of the year: Though the must less expensive and single volume Lancia and De Virgilio, At the Center by Geoffrey Goldberg came close, the Saoutchik epic more or less takes on all comers. But of course we have a solution: Best Italian subject book of 2014: Lancia and De Virgilio, Best French subject book, Saoutchik. A great year for books.

|